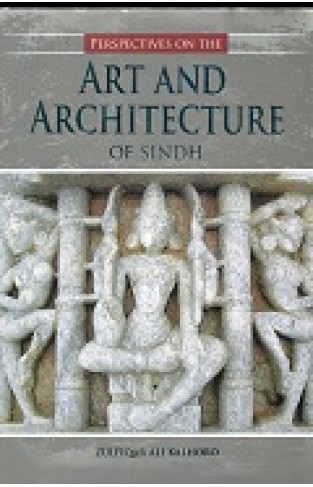

Perspectives on the Art & Architecture of Sindh

By: Zulfiqar Ali Kalhoro

-

Rs 1,620.00

- Rs 1,800.00

- 10%

You save Rs 180.00.

Due to constant currency fluctuation, prices are subject to change with or without notice.

When the late Dr Salome Zajadacz-Hastenrath wrote her masterful book Chaukhandi Gräber in 1978, one would have thought that was the last word on this most elegant of funerary art forms to be found anywhere in Pakistan. Along came that utterly puerile work History on Tombstones by self-styled historian Ali Ahmed Brohi followed by the more significant work of archaeologist Khurshid Hasan. It was however Zajadacz-Hastenrath’s work that for long lit the Chaukhandi horizon bright, especially after a much abridged English translation of her original German appeared in 2003.

The recent work Perspectives on the Art and Architecture of Sindh by anthropologist Zulfiqar Ali Kalhoro of Quaid e Azam University is in the same league as Zajadacz-Hastenrath’s work. The earlier work traces the evolutionary path of the art of stone carving for funerary decoration in Sindh and southern Balochistan from the 14th century until the mid-19th century. It shows how the art spread from a rather simple form in 14th century Gujarat to Sindh where it blossomed into its exquisite fullness. Kalhoro’s work takes our existing knowledge several steps ahead.

Perspectives is a collection of fifteen papers either read at conferences or published in various journals within the country and abroad. Most of these essays, especially in the case of those on Sati and hero stones in Tharparkar, are first-time investigations. Sati, the ultimate trial by fire for a widow on her husband’s pyre, was, we are told, ‘an act of establishing the truth (sat)’. Kalhoro reveals the ancestor worship latent in the reverence accorded mahasati (Great Sati) and satimata (Mother Sati) stelae.

In tandem, hero stones depict the valour of the jhujhar – the warrior who continues to battle even after decapitation. Kalhoro shows that such death was a degrading compromise of the Rajput fighter’s spiritual and physical integrity to be redeemed only by revenge. Jhujhar stones therefore depict the headless warrior in combat.

When the late Dr Salome Zajadacz-Hastenrath wrote her masterful book Chaukhandi Gräber in 1978, one would have thought that was the last word on this most elegant of funerary art forms to be found anywhere in Pakistan. Along came that utterly puerile work History on Tombstones by self-styled historian Ali Ahmed Brohi followed by the more significant work of archaeologist Khurshid Hasan. It was however Zajadacz-Hastenrath’s work that for long lit the Chaukhandi horizon bright, especially after a much abridged English translation of her original German appeared in 2003.

The recent work Perspectives on the Art and Architecture of Sindh by anthropologist Zulfiqar Ali Kalhoro of Quaid e Azam University is in the same league as Zajadacz-Hastenrath’s work. The earlier work traces the evolutionary path of the art of stone carving for funerary decoration in Sindh and southern Balochistan from the 14th century until the mid-19th century. It shows how the art spread from a rather simple form in 14th century Gujarat to Sindh where it blossomed into its exquisite fullness. Kalhoro’s work takes our existing knowledge several steps ahead.

Perspectives is a collection of fifteen papers either read at conferences or published in various journals within the country and abroad. Most of these essays, especially in the case of those on Sati and hero stones in Tharparkar, are first-time investigations. Sati, the ultimate trial by fire for a widow on her husband’s pyre, was, we are told, ‘an act of establishing the truth (sat)’. Kalhoro reveals the ancestor worship latent in the reverence accorded mahasati (Great Sati) and satimata (Mother Sati) stelae.

In tandem, hero stones depict the valour of the jhujhar – the warrior who continues to battle even after decapitation. Kalhoro shows that such death was a degrading compromise of the Rajput fighter’s spiritual and physical integrity to be redeemed only by revenge. Jhujhar stones therefore depict the headless warrior in combat.

Perspectives On The Art And Architecture Of Sindh -

By: Zulfiqar Ali Kalhoro

Rs 1,530.00 Rs 1,800.00 Ex Tax :Rs 1,530.00

Symbols in Stone: The Rock Art of Sindh

By: Zulfiqar Ali Kalhoro

Rs 1,080.00 Rs 1,200.00 Ex Tax :Rs 1,080.00

Perspectives on the Art & Architecture of Sindh

By: Zulfiqar Ali Kalhoro

Rs 1,620.00 Rs 1,800.00 Ex Tax :Rs 1,620.00

Zubin Mehta: A Musical Journey (An Authorized Biography)

By: VOID - Bakhtiar K. Dadabhoy

Rs 892.50 Rs 1,050.00 Ex Tax :Rs 892.50

Perspectives On The Art And Architecture Of Sindh -

By: Zulfiqar Ali Kalhoro

Rs 1,530.00 Rs 1,800.00 Ex Tax :Rs 1,530.00

Perspectives On The Art And Architecture Of Sindh -

By: Zulfiqar Ali Kalhoro

Rs 1,530.00 Rs 1,800.00 Ex Tax :Rs 1,530.00

Zubin Mehta: A Musical Journey (An Authorized Biography)

By: VOID - Bakhtiar K. Dadabhoy

Rs 892.50 Rs 1,050.00 Ex Tax :Rs 892.50

Perspectives On The Art And Architecture Of Sindh -

By: Zulfiqar Ali Kalhoro

Rs 1,530.00 Rs 1,800.00 Ex Tax :Rs 1,530.00

Symbols in Stone: The Rock Art of Sindh

By: Zulfiqar Ali Kalhoro

Rs 1,080.00 Rs 1,200.00 Ex Tax :Rs 1,080.00

Perspectives on the Art & Architecture of Sindh

By: Zulfiqar Ali Kalhoro

Rs 1,620.00 Rs 1,800.00 Ex Tax :Rs 1,620.00

Perspectives On The Art And Architecture Of Sindh -

By: Zulfiqar Ali Kalhoro

Rs 1,530.00 Rs 1,800.00 Ex Tax :Rs 1,530.00

-120x187.jpg?q6)