- Home

- Books

- Sale

- 11.11 Sale UPTO 90% OFF

- 20% OFF

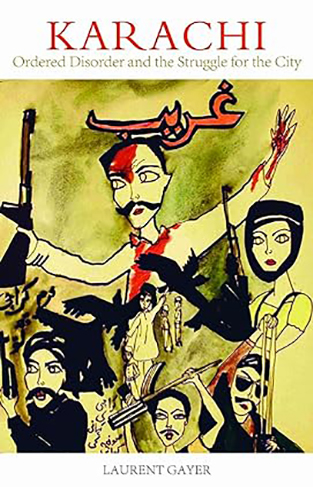

- Karachi Ordered Disorder and the Struggle for the City

Karachi Ordered Disorder and the Struggle for the City

By: Laurent Gayer

-

Rs 1,356.00

- Rs 1,695.00

- 20%

You save Rs 339.00.

Due to constant currency fluctuation, prices are subject to change with or without notice.

With a population exceeding twenty million, Karachi is one of the world’s largest ‘megacities’. It is also one of the most violent.

Since the mid-1980s, Karachi has endured endemic political conflict and criminal violence, which revolve around control of the city and its resources (votes, land and bhatta — ‘protection’ money). These struggles for the city have become ethnicised. In the process, Karachi, often referred to as a ‘Pakistan in miniature’, has become increasingly fragmented, socially as well as territorially.

Despite this chronic state of urban political warfare, Karachi remains the cornerstone of the economy of Pakistan. In contrast to the ‘chaotic’ and ‘anarchic’ city portrayed in journalistic accounts, there is indeed order of a kind in the city’s permanent civil war.

Far from being entropic, Karachi’s polity is predicated upon relatively stable patterns of domination, rituals of interaction and forms of arbitration, which have made violence manageable for its population — even if this does not exclude a pervasive state of fear, which results from the continuous transformation of violence in the course of its updating. Whether such ‘ordered disorder’ is viable in the long term remains to be seen, but for now Karachi works despite — and sometimes through — violence

With a population exceeding twenty million, Karachi is one of the world’s largest ‘megacities’. It is also one of the most violent.

Since the mid-1980s, Karachi has endured endemic political conflict and criminal violence, which revolve around control of the city and its resources (votes, land and bhatta — ‘protection’ money). These struggles for the city have become ethnicised. In the process, Karachi, often referred to as a ‘Pakistan in miniature’, has become increasingly fragmented, socially as well as territorially.

Despite this chronic state of urban political warfare, Karachi remains the cornerstone of the economy of Pakistan. In contrast to the ‘chaotic’ and ‘anarchic’ city portrayed in journalistic accounts, there is indeed order of a kind in the city’s permanent civil war.

Far from being entropic, Karachi’s polity is predicated upon relatively stable patterns of domination, rituals of interaction and forms of arbitration, which have made violence manageable for its population — even if this does not exclude a pervasive state of fear, which results from the continuous transformation of violence in the course of its updating. Whether such ‘ordered disorder’ is viable in the long term remains to be seen, but for now Karachi works despite — and sometimes through — violence

Karachi Ordered Disorder and the Struggle for the City

By: Laurent Gayer

Rs 1,356.00 Rs 1,695.00 Ex Tax :Rs 1,356.00

Zubin Mehta: A Musical Journey (An Authorized Biography)

By: VOID - Bakhtiar K. Dadabhoy

Rs 472.50 Rs 1,050.00 Ex Tax :Rs 472.50

Issues in Pakistan's Economy - A Political Economy Perspective

By: S. Akbar Zaidi

Rs 1,836.00 Rs 2,295.00 Ex Tax :Rs 1,836.00

Economy, Welfare, and Reforms in Pakistan. Essays in Honour of Dr Ishrat Husain

By: Vaqar Ahmed

Rs 876.00 Rs 1,095.00 Ex Tax :Rs 876.00

Karachi’s Public Transport - Origins, Evolution, and Future Planning

By: Arif Hasan

Rs 732.00 Rs 915.00 Ex Tax :Rs 732.00

Myths Illusions and Peace: Finding a New Direction for America in the Middle East

By: Dennis Ross

Rs 876.00 Rs 1,095.00 Ex Tax :Rs 876.00

The Origins of Political Order From Prehuman Times to the French RevolutioN

By: Francis Fukuyama

Rs 3,116.00 Rs 3,895.00 Ex Tax :Rs 3,116.00

Manning Up: How the Rise of Women Has Turned Men into Boys

By: Kay Hymowitz

Rs 646.75 Rs 995.00 Ex Tax :Rs 646.75

The Obama Syndrome: Surrender At Home War Abroad

By: Tariq Ali

Rs 1,036.00 Rs 1,295.00 Ex Tax :Rs 1,036.00

The Quest For Meaning: Developing A Philosophy Of Pluralism

By: Tariq Ramadan

Rs 1,116.00 Rs 1,395.00 Ex Tax :Rs 1,116.00

Issues in Pakistan's Economy - A Political Economy Perspective

By: S. Akbar Zaidi

Rs 1,836.00 Rs 2,295.00 Ex Tax :Rs 1,836.00

Economy, Welfare, and Reforms in Pakistan. Essays in Honour of Dr Ishrat Husain

By: Vaqar Ahmed

Rs 876.00 Rs 1,095.00 Ex Tax :Rs 876.00

Karachi’s Public Transport - Origins, Evolution, and Future Planning

By: Arif Hasan

Rs 732.00 Rs 915.00 Ex Tax :Rs 732.00

No recently viewed books available at the moment.

Zubin Mehta: A Musical Journey (An Authorized Biography)

By: VOID - Bakhtiar K. Dadabhoy

Rs 472.50 Rs 1,050.00 Ex Tax :Rs 472.50

Karachi Ordered Disorder and the Struggle for the City

By: Laurent Gayer

Rs 1,356.00 Rs 1,695.00 Ex Tax :Rs 1,356.00

Issues in Pakistan's Economy - A Political Economy Perspective

By: S. Akbar Zaidi

Rs 1,836.00 Rs 2,295.00 Ex Tax :Rs 1,836.00

Economy, Welfare, and Reforms in Pakistan. Essays in Honour of Dr Ishrat Husain

By: Vaqar Ahmed

Rs 876.00 Rs 1,095.00 Ex Tax :Rs 876.00

Karachi’s Public Transport - Origins, Evolution, and Future Planning

By: Arif Hasan

Rs 732.00 Rs 915.00 Ex Tax :Rs 732.00

-120x187.jpg?q6)

-120x187.jpg?q6)

-120x187.jpg?q6)