- Home

- Books

- Categories

- Non Fiction

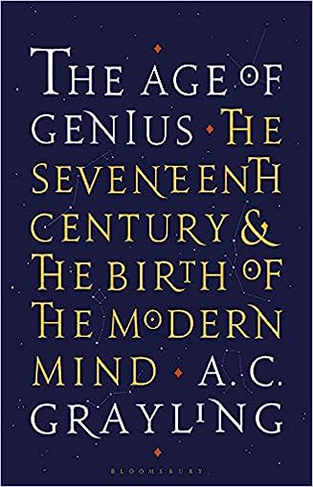

- The Age of Genius - The Seventeenth Century and the Birth of the Modern Mind

The Age of Genius - The Seventeenth Century and the Birth of the Modern Mind

By: A. C. Grayling

-

Rs 2,726.75

- Rs 4,195.00

- 35%

You save Rs 1,468.25.

Due to constant currency fluctuation, prices are subject to change with or without notice.

Bestselling author A. C. Grayling explains how--fueled by original and unorthodox thinking, war, and technological invention--the seventeenth century became the crucible of modernity.

What happened to the European mind between 1605, when an audience watching Macbeth at the Globe might believe that regicide was such an aberration of the natural order that ghosts could burst from the ground, and 1649, when a large crowd, perhaps including some who had seen Macbeth forty-four years earlier, could stand and watch the execution of a king? Or consider the difference between a magus casting a star chart and the day in 1639 when Jonathan Horrock and William Crabtree watched the transit of Venus across the face of the sun from their attic, successfully testing its course against Kepler's Tables of Planetary Motion, in a classic case of confirming a scientific theory by empirical testing.

In this turbulent period, science moved from the alchemy and astrology of John Dee to the painstaking observation and astronomy of Galileo, from the classicism of Aristotle, still favored by the Church, to the evidence-based, collegiate investigation of Francis Bacon. And if the old ways still lingered and affected the new mindset--Descartes's dualism an attempt to square the new philosophy with religious belief; Newton, the man who understood gravity and the laws of motion, still fascinated to the end of his life by alchemy--by the end of that tumultuous century "the gre

Bestselling author A. C. Grayling explains how--fueled by original and unorthodox thinking, war, and technological invention--the seventeenth century became the crucible of modernity.

What happened to the European mind between 1605, when an audience watching Macbeth at the Globe might believe that regicide was such an aberration of the natural order that ghosts could burst from the ground, and 1649, when a large crowd, perhaps including some who had seen Macbeth forty-four years earlier, could stand and watch the execution of a king? Or consider the difference between a magus casting a star chart and the day in 1639 when Jonathan Horrock and William Crabtree watched the transit of Venus across the face of the sun from their attic, successfully testing its course against Kepler's Tables of Planetary Motion, in a classic case of confirming a scientific theory by empirical testing.

In this turbulent period, science moved from the alchemy and astrology of John Dee to the painstaking observation and astronomy of Galileo, from the classicism of Aristotle, still favored by the Church, to the evidence-based, collegiate investigation of Francis Bacon. And if the old ways still lingered and affected the new mindset--Descartes's dualism an attempt to square the new philosophy with religious belief; Newton, the man who understood gravity and the laws of motion, still fascinated to the end of his life by alchemy--by the end of that tumultuous century "the gre

The Age of Genius: The Seventeenth Century and the Birth of the Modern Mind

By: A. C. Grayling

Rs 1,812.25 Rs 3,295.00 Ex Tax :Rs 1,812.25

The Frontiers of Knowledge: What We Know About Science, History and The Mind

By: A. C. Grayling

Rs 1,975.50 Rs 2,195.00 Ex Tax :Rs 1,975.50

For the Good of the World: Is Global Agreement on Global Challenges Possible?

By: A. C. Grayling

Rs 1,922.25 Rs 3,495.00 Ex Tax :Rs 1,922.25

For the Good of the World - Is Global Agreement on Global Challenges Possible?

By: A. C. Grayling

Rs 1,881.75 Rs 2,895.00 Ex Tax :Rs 1,881.75

The Age of Genius - The Seventeenth Century and the Birth of the Modern Mind

By: A. C. Grayling

Rs 2,726.75 Rs 4,195.00 Ex Tax :Rs 2,726.75

Philosophy and Life: Exploring the Great Questions of How to Live

By: A. C. Grayling

Rs 2,396.00 Rs 2,995.00 Ex Tax :Rs 2,396.00

Zubin Mehta: A Musical Journey (An Authorized Biography)

By: VOID - Bakhtiar K. Dadabhoy

Rs 472.50 Rs 1,050.00 Ex Tax :Rs 472.50

The Origins of Political Order From Prehuman Times to the French RevolutioN

By: Francis Fukuyama

Rs 3,505.50 Rs 3,895.00 Ex Tax :Rs 3,505.50

Manning Up: How the Rise of Women Has Turned Men into Boys

By: Kay Hymowitz

Rs 646.75 Rs 995.00 Ex Tax :Rs 646.75

The Obama Syndrome: Surrender At Home War Abroad

By: Tariq Ali

Rs 1,165.50 Rs 1,295.00 Ex Tax :Rs 1,165.50

The Quest For Meaning: Developing A Philosophy Of Pluralism

By: Tariq Ramadan

Rs 1,255.50 Rs 1,395.00 Ex Tax :Rs 1,255.50

The Pakistan US Conundrum Jihadists The Military And The People The Struggle For Control

By: Yunas Samad

Rs 1,255.50 Rs 1,395.00 Ex Tax :Rs 1,255.50

An Enemy We Created: The Myth Of The Taliban Al Qaeda Merger In Afghanistan 19702010

By: Alex Strick van Linschoten

Rs 3,412.50 Rs 5,250.00 Ex Tax :Rs 3,412.50

WikiLeaks: Inside Julian Assanges War on Secrecy

By: David Leigh & Luke Harding

Rs 552.50 Rs 850.00 Ex Tax :Rs 552.50

No similar books from this author available at the moment.

No recently viewed books available at the moment.

Zubin Mehta: A Musical Journey (An Authorized Biography)

By: VOID - Bakhtiar K. Dadabhoy

Rs 472.50 Rs 1,050.00 Ex Tax :Rs 472.50

The Age of Genius: The Seventeenth Century and the Birth of the Modern Mind

By: A. C. Grayling

Rs 1,812.25 Rs 3,295.00 Ex Tax :Rs 1,812.25

The Frontiers of Knowledge: What We Know About Science, History and The Mind

By: A. C. Grayling

Rs 1,975.50 Rs 2,195.00 Ex Tax :Rs 1,975.50

For the Good of the World: Is Global Agreement on Global Challenges Possible?

By: A. C. Grayling

Rs 1,922.25 Rs 3,495.00 Ex Tax :Rs 1,922.25

For the Good of the World - Is Global Agreement on Global Challenges Possible?

By: A. C. Grayling

Rs 1,881.75 Rs 2,895.00 Ex Tax :Rs 1,881.75

The Age of Genius - The Seventeenth Century and the Birth of the Modern Mind

By: A. C. Grayling

Rs 2,726.75 Rs 4,195.00 Ex Tax :Rs 2,726.75

Philosophy and Life: Exploring the Great Questions of How to Live

By: A. C. Grayling

Rs 2,396.00 Rs 2,995.00 Ex Tax :Rs 2,396.00

-120x187.jpg?q6)

-120x187.jpg?q6)

-120x187.jpg?q6)