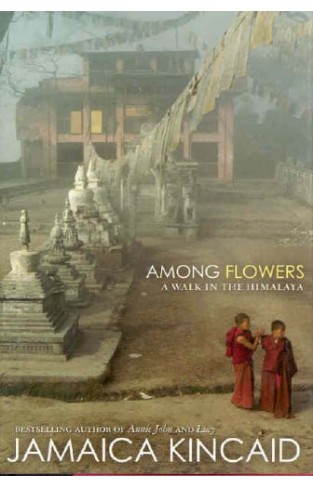

We're offering a high

discount on this book as it is slightly damaged

"This account of a walk I took while gathering the seeds of flowering plants in the foothills of the Himalayas has its origins in my love of the gardenmy love of feeling isolated, of imagining myself all alone in the world and everything unfamiliar, or the familiar being strange, my love of being afraid but at the same time not letting my fear stand in the way." So begins Jamaica Kincaid's adventure into the mountains of Nepal with a small group of botanists. After laborious training and preparation, the group leaves Kathmandu by small plane, into the Annapurna Valley to begin their trek. ("From inside the plane it always seemed to me as if we were about to collide with these sharp green peaks, I especially thought this would be true when I saw one of the pilots reading the newspaper, but Dan said that at the other times he'd flown in this part of the world the pilots always read the newspaper and it did not seem to affect the flight in a bad way.") The temperature was 96 degrees F. on arrival, and the little airport in Tumlingtar was awash in Maoists in camouflage fatigues. "What I was about to do, what I had in mind to do, what I planned for over a year to do, was still a mystery to me. I was on the edge of it though." The group sets off with a large retinue of sherpas and bearers, and Kincaid, in simple, richly detailed prose describes the landscape, the Nepalese villages, the passing trekkers and yak herds. Direct and opinionated ("We decided to call them [other trekkers] the Germans because we didn't like them from the look of themand Germans seem to be the one group of people left that cannot be liked because you feel like it."), Kincaid moves easily between closely observed, down-to-earth descriptions of the trek and larger musings, about gardens, nature, seed gathering, home, and family. Negotiations with the Maoists to pass through villages interject dramatic notes ("Dan and I became Canadians. Until then I would never have dreamt of calling myself anything other than American. But the Maoists had told Sunam [head sherpa] that President Powell had just been to Kathmandu and denounced them as terrorists and that had made them very angry with President Powell."). The group presses on, determined in its search for "beautiful plants native to the Himalayas but will grow happily in Vermont or somewhere like that." Eventually they reach a spectacular pass at 15,600 feet and start back. Down at the village of Donge they have another run-in with the Maoists. They "lectured us all through the afternoon into the setting sun, mentioning again the indignity of being called mere terrorists by President Powell of the United States." To lessen the tension, the sherpas produces some Chang, an alcohol made from millet, intoxicating everyone, Kincaid included. At the airport, the Maoists are threatening attack, but the group must wait three days for an airplane. Finally they get off safely. "Days later, in Kathmandu, we heard that the very airport where we had camped for days had been attacked by Maoists and some people had been killed." In Kathmandu another Maoist attack closes the city down. "As we waited to leave this place, I remembered the carpet of gentiansand the isolated but thick patches of Delphinium abloom in the melting snow. There were the forests of rhododendrons, specimens thirty feet highI remembered all that I had seen but I especially remembered all that I had felt. I remembered my fears. I remembered how practically every step was fraught with memories of my past, and the immediate one of my son Harold all alone in Vermont, and my love for it and my fear of losing it." "This account of a walk I took while gathering the seeds of flowering plants in the foothills of the Himalayas has its origins in my love of the gardenmy love of feeling isolated, of imagining myself all alone in the world and everything unfamiliar, or the familiar being strange, my love of being afraid but at the same time not letting my fear stand in the way." So begins Jamaica Kincaid's adventure into the mountains of Nepal with a small group of botanists. After laborious training and preparation, the group leaves Kathmandu by small plane, into the Annapurna Valley to begin their trek. ("From inside the plane it always seemed to me as if we were about to collide with these sharp green peaks, I especially thought this would be true when I saw one of the pilots reading the newspaper, but Dan said that at the other times he'd flown in this part of the world the pilots always read the newspaper and it did not seem to affect the flight in a bad way.") The temperature was 96 degrees F. on arrival, and the little airport in Tumlingtar was awash in Maoists in camouflage fatigues. "What I was about to do, what I had in mind to do, what I planned for over a year to do, was still a mystery to me. I was on the edge of it though." The group sets off with a large retinue of sherpas and bearers, and Kincaid, in simple, richly detailed prose describes the landscape, the Nepalese villages, the passing trekkers and yak herds. Direct and opinionated ("We decided to call them [other trekkers] the Germans because we didn't like them from the look of themand Germans seem to be the one group of people left that cannot be liked because you feel like it."), Kincaid moves easily between closely observed, down-to-earth descriptions of the trek and larger musings, about gardens, nature, seed gathering, home, and family. Negotiations with the Maoists to pass through villages interject dramatic notes ("Dan and I became Canadians. Until then I would never have dreamt of calling myself anything other than American. But the Maoists had told Sunam [head sherpa] that President Powell had just been to Kathmandu and denounced them as terrorists and that had made them very angry with President Powell."). The group presses on, determined in its search for "beautiful plants native to the Himalayas but will grow happily in Vermont or somewhere like that." Eventually they reach a spectacular pass at 15,600 feet and start back. Down at the village of Donge they have another run-in with the Maoists. They "lectured us all through the afternoon into the setting sun, mentioning again the indignity of being called mere terrorists by President Powell of the United States." To lessen the tension, the sherpas produces some Chang, an alcohol made from millet, intoxicating everyone, Kincaid included. At the airport, the Maoists are threatening attack, but the group must wait three days for an airplane. Finally they get off safely. "Days later, in Kathmandu, we heard that the very airport where we had camped for days had been attacked by Maoists and some people had been killed." In Kathmandu another Maoist attack closes the city down. "As we waited to leave this place, I remembered the carpet of gentiansand the isolated but thick patches of Delphinium abloom in the melting snow. There were the forests of rhododendrons, specimens thirty feet highI remembered all that I had seen but I especially remembered all that I had felt. I remembered my fears. I remembered how practically every step was fraught with memories of my past, and the immediate one of my son Harold all alone in Vermont, and my love for it and my fear of losing it."