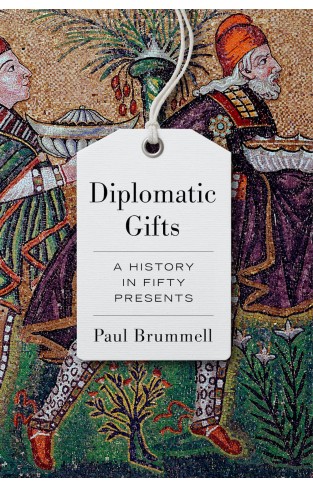

The giving of gifts has been associated with diplomacy from ancient times to the present. Press coverage tends to focus on examples which highlight cultural differences between giver; where a gift is perceived as excessive, sometimes with connotations of bribery; or where the gift poses particular challenges. The latter is exemplified by a gift in Mali of a camel to French President Francois Hollande in 2013, where the international media gleefully reported that the unfortunate creature had ended up in a tajine.Using the examples of fifty diplomatic gifts through the ages, Brummell explains how the art of diplomatic gift giving is a highly complex affair, based around objectives set by the giver, though rarely so duplicitously as in the case of perhaps the most famous diplomatic gift of all, the Trojan Horse. Another example is the use of Sevres porcelain by Kings Louis XV and XVI of France and of the favouring of Faberge for diplomatic gifts from the Russian Royal Family in promoting the fame and success of these 'brands'. The choice of diplomatic gift is usually accompanied by some attempt to understand the character and interests of the recipient, to identify a gift which will be particularly welcome. The gifting by Adolf Hitler of the remains of Napoleon II to France in 1940 was in part an attempt to help shore up the legitimacy of the Vichy regime. In some cases the influence of the receiver on the choice of gift is greater, extending to the recipient making clear the nature of the gift desired. An early example of around 1350BC from the Amarna Letters involves a communication from Hittite Prince Zita to the Egyptian Pharaoh, offering a gift of sixteen men and hinting rather heavily that he would like some gold in return. The gifting of Cleopatra's Needle to the United Kingdom from the Ottoman Governor of Egypt is also discussed in this context.